Acoustic Guitar Guide: Aren't all guitars just ... guitar shaped?

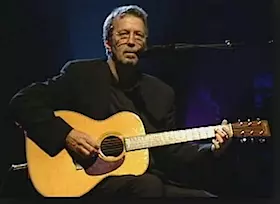

C.F. Martin & Co. established size categories early on for the range of increasingly large guitars the company has produced since it's founding in 1833. Pictured above (left to right): classic Martin "Style 28" guitars with spruce tops, rosewood backs and sides, and ebony fretboards.

At first glance, acoustic guitars can look pretty much all the same. But in fact they come in all sorts of sizes, styles and shapes, which can have a dramatic effect on volume, tone, and playability.

There is no easy way to categorize guitars. With a confusing multitude of same but different model naming conventions across different brands, which have been loosely adhered to and often redefined over time, any attempt at classification inevitably results in more exceptions than rules.

However, says luthier Dick Boak, having played around with thousands of acoustic guitars of different sizes, shapes and tonewoods over his 33-year career at C. F. Martin & Co., "we can at least make some generalizations about small versus large guitars."

Bigger guitars with more voluminous air chambers are generally louder and capable of deeper bass response, while smaller and shallower bodied guitars, in addition to being less cumbersome to carry and hold, are favoured for their brightness, clarity, and even balance of bass and treble.

"People expect big guitars to have a big sound," says Boak, "and expect small guitars to be somehow diminished in tone. But smaller instruments can be disproportionately and shockingly powerful in their volume. Without excessive bass overtones or woofiness, smaller guitars can be less prone to feedback onstage, and because it is easier to add bass than subtract it in the studio, smaller guitars are typically capable of producing a cleaner recording."

Scale Length

Guitar strings stretch from the nut at the top of the neck, down to the saddle and bridge. This distance is the scale length. Steel string acoustic guitars commonly have scale lengths that range from 24-inches (610 mm) on short-scale instruments to 25.5-inches (648 mm) on full-scale instruments. The distance from the top nut to the 12th "octave fret" marks the exact mid-point.

Scale length effects intonation, tuning, tone, and string tension.

Longer scale lengths at the same pitch put strings under greater tension, while shorter scale lengths can be more easily tuned to higher pitches.

Both guitars have virtually the same body shape, but

Martin's 000-28 is traditionally short scale (24.9") while its

kissing cousin OM-28 is long scale (25.4").

J-45 "Workhorse", and classic small-body L-00.

To illustrate the effect of scale length on string tension, if you capo a standard acoustic guitar at the 1st fret, it effectively shortens the scale length by about 1 1/2-inches, and raises the pitch of each string by a semi-tone.

To restore the guitar to standard pitch, you tune each string down a half-step. The result is significantly less string tension.

Explains Boak, "The strings will be noticeably looser, more sensitive to the touch, more bendable, and with perhaps a bit less volume or punch. So a player who wants the greatest volume and projection might gravitate toward a longer scale instrument, while a player who wants the more delicate expressiveness of note bending might prefer a shorter scale instrument".

Another important distinction between guitars is whether they have 12 or 14 frets above the body. The 12-fret body design was standard until the 1930s, its longer body produces more bass, volume and presence.

"The extra body space above the soundhole on 12-fret guitars adds a hollowness to the tone that fingerstyle players like," says Boak but isn't as beneficial for strumming".

Buying a guitar starts with one that feels right

Look for a guitar with an appropriate body size and shape, and with a neck that isn't too big to get your hands around.

The only way to be sure is to try out a variety of guitars and choose one that is naturally comfortable to hold, standing up with a strap, or in your lap sitting down.

If you are new to the instrument, or uncertain, ask a professional salesperson, teacher, or more experienced player to help steer you in the right direction.

It's no different than buying a bicycle or a new pair of shoes, the wrong fit can really work against you.

Concludes Boak, "Every guitar has its own personality. An understanding of how the design variables can effect its sound and feel will help you focus on finding the right instrument".

When the shoe fits ...

Parlor/Concert/O: Popular in the early 1900s, and treasured by 60s folk players such as Joan Baez, traditional "baby" size Parlor guitars are easy to carry and hold, and can be surprisingly loud for their size. They have a light, balanced tone making them ideal for light fingerpicking.

Gibson L/00: A standard established in the early-19th century, and modeled after the round shouldered classical guitar bodies of the day, they have a bright, rootsy sound, are comfortable to play standing or sitting, and can be a good choice for youngsters or players with smaller hands.

Martin 000-28.

Auditorium/OOO/Orchestra Model(OM): Wider and deeper than a Grand Concert, this is the quintessential "small-body" guitar with an excellent balance of volume, tone and playability. Some models have a more deeply rounded back, which adds volume to the soundbox without increasing depth.

Taylor Dreadnought.

Dreadnought: Introduced in the 1920s, and named after the most fearsome British battleship of the day, Dreadnoughts were made to be heard over other barn-dance instruments like banjos and fiddles. Their deep, resonant sound makes them ideal for both flatpicking and finger-style playing.

and Epiphone EJ-200.

Jumbo/Super Jumbo: Similar in shape to Auditorium guitars, Jumbos are massive sounding rhythm guitars with lots of volume, deep bass, and sparkling overtones. They are popular with country music players, who refer to them as "country blues machines", or "the flat-top to beat".